This article was originally published on ProductLed.org.

Today, all modern software organizations know about and use conversion optimization tactics like A/B testing. The rise of low- and no-code conversion tooling has made it easier than ever to get started. The downside is that many more (new) growth teams start testing without first even developing a strategy. Sound familiar?

Take for example a team tasked with increasing new customer acquisition. Lacking the correct optimization strategy, the growth team may focus only on the part of the funnel that they own (e.g. the “growth marketing team” only focusing on marketing pages). Alternatively, the growth team may start with a specific part of the process because they want to “show impact by focusing on low-hanging fruit” (e.g. optimizing a sign-up form that has too many fields because more form fields always equals lower conversion).

Sure, the team may be able to demonstrate an improvement with this approach. But without a solid optimization strategy, they may ultimately end up with a sub-optimized funnel. In other words, the team will leave opportunity on the table. There is a better approach.

As a strategic growth leader, your goal is not to simply improve a conversion rate, your goal is to maximize throughput of the funnel. To accomplish this, you need to work across multiple steps of the funnel, in the correct order.

The question is, of course, “what is the correct approach to maximize funnel throughput?” Enter the Theory of Constraints.

The Theory of Constraints

The theory of constraints (TOC) is a management philosophy for optimizing throughput of a system. TOC says that a system consists of many linked activities and one—and only one—of those activities acts as a bottleneck (constraint) that reduces the throughput of the entire system. To optimize throughput of the system, the theory of constraints asserts that managers must identify the single most important limiting factor (i.e. constraint) that inhibits the achievement of the goal.

Interestingly, there are not hundreds of constraints—just one. The single activity which most inhibits throughput is the constraint. You must systematically improve (reduce) the constraint to maximize throughput.

How to Maximize Throughput

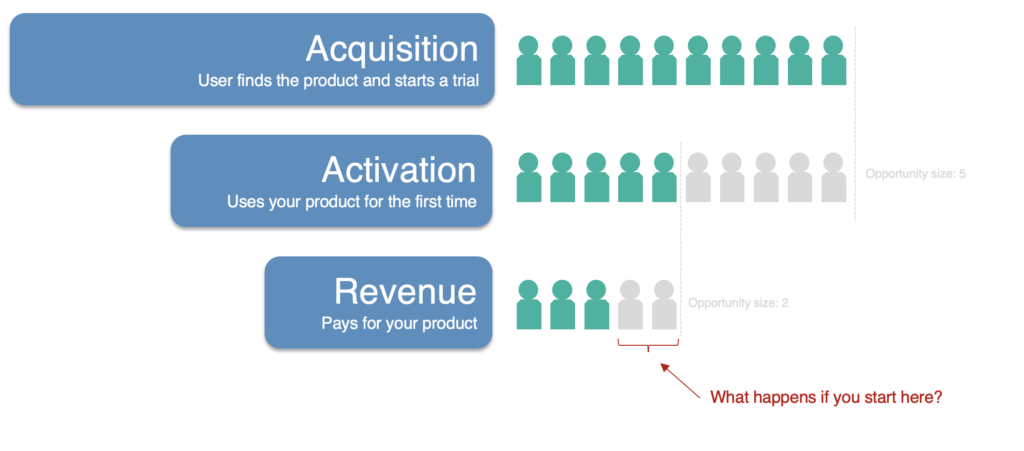

To illustrate the concept of theory of constraints applied to new customer acquisition, let’s take a look at a basic funnel using the Pirate Metrics Framework. To best illustrate the concept, I will use small numbers and a simplified version of the framework.

Example 1: Maximize Throughput of New Paying Customers

To illustrate the concept of theory of constraints applied to new customer acquisition, let’s take a look at a basic funnel using the Pirate Metric Framework. The Pirate Metric Framework tracks users through their journey in the product. In this example, since we are focused on new customer acquisition, we will focus on a simplified subset of the framework. The example will use small numbers to easily illustrate the concept: Acquisition: 10 prospects start a trial

- Acquisition: 10 prospects start a trial

- Activation: 5 prospects use the product for the first time

- Revenue: 3 prospects become paying customers

For the purpose of this example, let us define a few terms:

- Total Funnel Size: the total amount of people who come through the funnel

- Opportunity size: at each step of the funnel, the people who drop-off and could be potentially recaptured

- Yield: the total number of paying customers produced by the funnel

- Maximum potential yield: the potential number of paying customers that the funnel can produce at the final step

Starting with a funnel of 10, and the variables above, your maximum potential yield (maximum new paid customers) is 5.

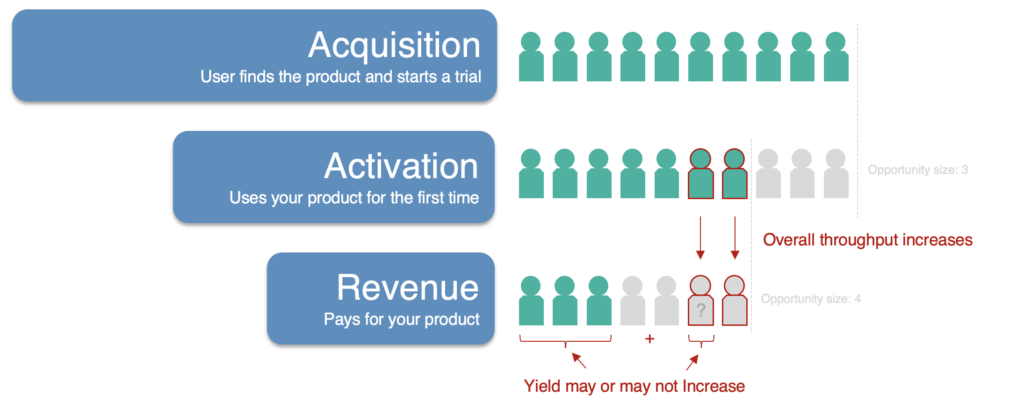

Example 1: Start with any step

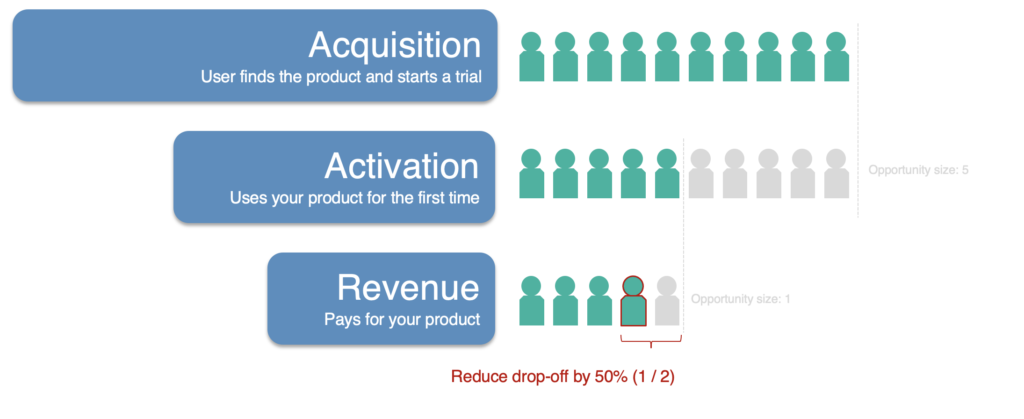

Let’s take a look at what happens if you start at any step, in this case, the revenue step. As you will see, you can increase yield but you do not fundamentally change the potential for future growth.

Your team works to diligently understand the cause of the drop-off and is able to reduce the drop by 50%. Congrats!

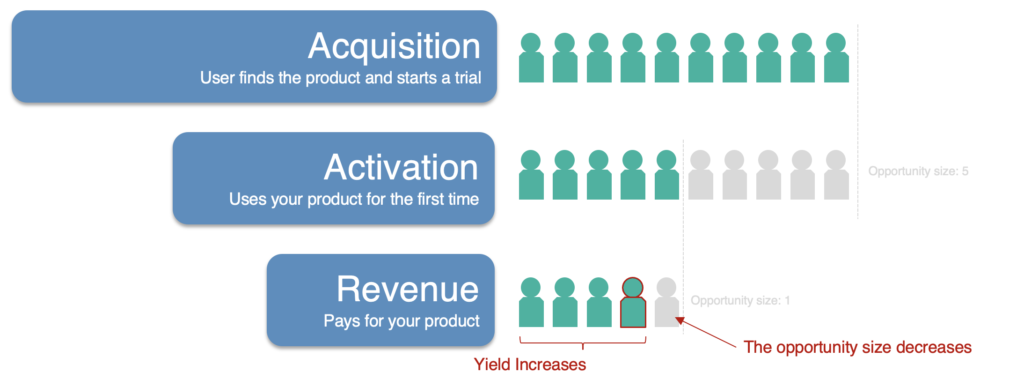

The yield (number of new paying customers) of the funnel increases from 3 to 4. The opportunity size at the revenue step also decreases.

Why does this matter? The opportunity size is the amount of opportunity that you have to continue optimizing the throughput of your funnel. In this case, the opportunity size is the number of customers we are losing at the bottom of the funnel. The team’s ability to further improve the funnel yield will decrease because it becomes much more difficult to improve conversion further as the conversion rate approaches 100% at the revenue step.

The funnel started with a maximum potential yield of 5. After dedicated focus by the team, the yield (the number of paying customers) increased from 3 to 4, but the maximum potential yield remained unchanged at 5. The team must now work harder to achieve further gains, which the team is also less likely to achieve.

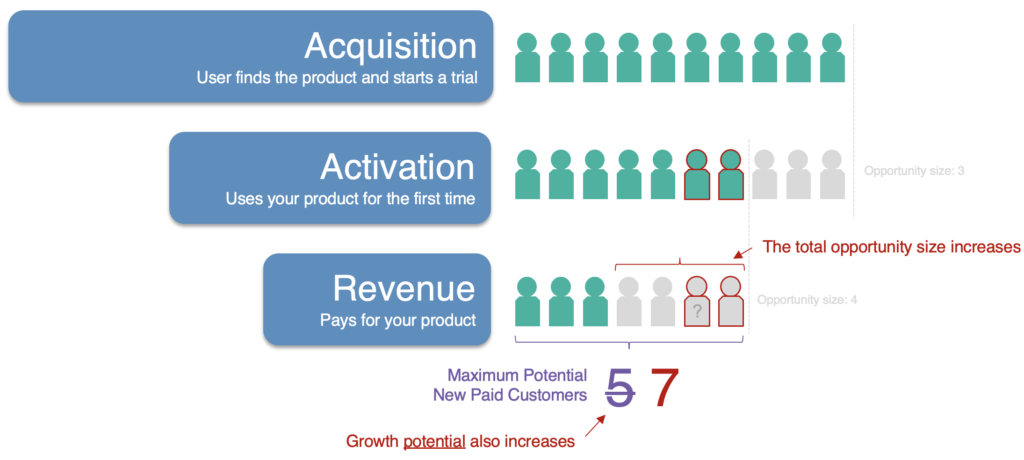

Example 2: Start with the constraint

Taking a cue from the theory of constraints, let us now look at what happens if you start with the constraint. The funnel loses 5 (50%) at the activation step whereas the funnel only loses 2 (20%) at the revenue step. The constraint is the activation step. Let us see what happens when we start with the constraint.

The team works diligently to reduce drop off in the activation step by 50%. Amazing.

With the reduction in drop-off at the activation step, you will see that the throughput at the activation stage increases.

In some cases you will also find that yield (the number of prospects who convert to paying customers) will also increase as they move beyond the activation step. As you will see in a moment, it also increases the opportunity size at the revenue step. That said, it is important to note that improving activation does not always improve the yield.

A brief digression for a moment. You may ask, “why doesn’t yield automatically increase as you improve throughput at activation?” Generally speaking, prospects who make it through your funnel and become paying customers are the most motivated to get through the steps.

These prospects are more motivated to invest time to learn the product, overcome potential challenges using your product, and ultimately, pay for your product. The converse is also true. Compared to the prospects who became paying customers, those prospects who did not were relatively less motivated to learn the product, overcome challenges, or pay for your product. In other words, all prospects aren’t all equally motivated to pay.

Regardless of whether or not yield increases, you are now better positioned to improve the revenue step because prospects who don’t use the product are extremely unlikely to pay for the product. The improved funnel has more prospects who are deciding whether or not to purchase the product. In other words, improving activation also changes the dynamics of the funnel by increasing maximum potential yield.

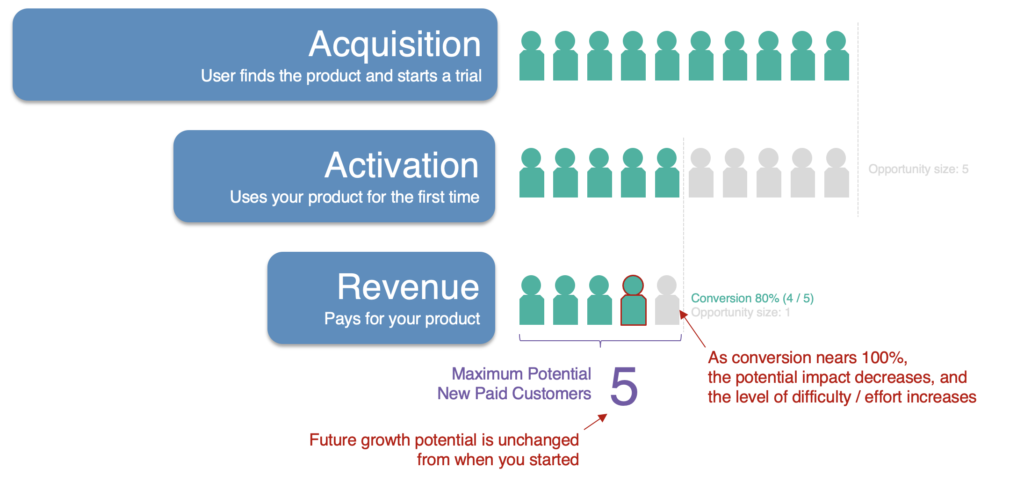

In the first example, the maximum potential yield of the funnel remained at 5. In this next example, the maximum potential yield has now increased to 7 by first improving the activation step. The opportunity size for improving yield at the revenue step has also increased to 4, meaning you can potentially see greater impact by reducing drop off at this step.

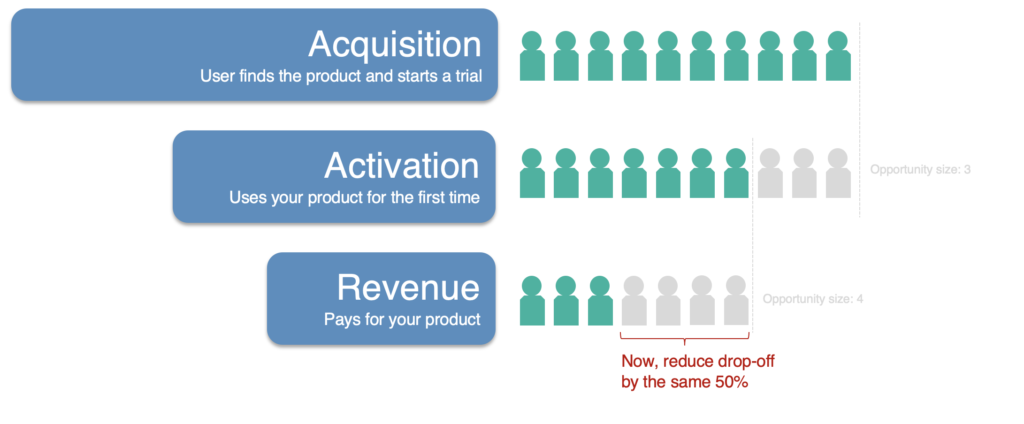

To illustrate the opportunity at the revenue step on the funnel, consider the same 50% improvement at the revenue step (recall, the first example showed a 50% reduction at the revenue step).

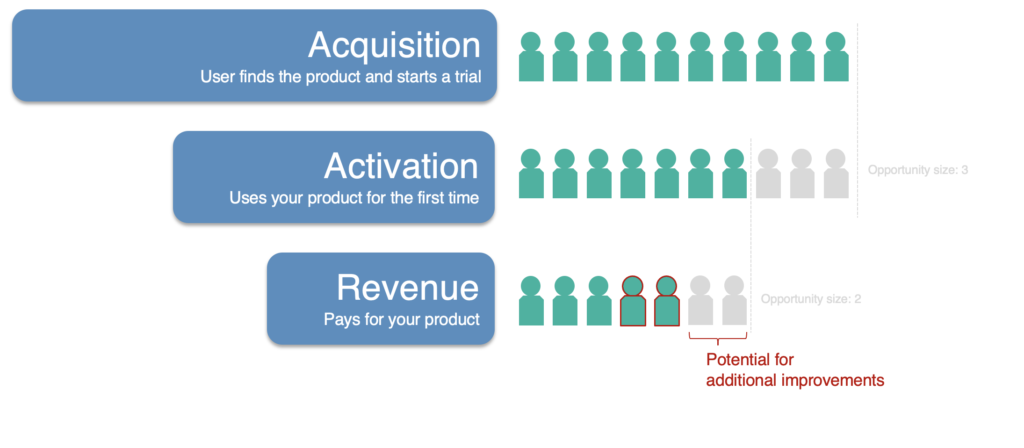

A 50% reduction in drop off with the new funnel results in double the yield. The improvement gives us 2 new paying customers compared to the initial example of 1.

Also look at the opportunity size at the revenue step. You will also recall from the earlier example that it becomes increasingly difficult to improve conversion as you near 100%. In this new example (again, focusing initially on activation first then reducing drop-off at the revenue step), you see that there is still additional room for improvement with an opportunity size of 2 versus 1 from the earlier example.

The examples above clearly demonstrate in terms of yield as well as maximum potential yield—that it’s optimal to follow the theory of constraints. That is, to reduce the constraint as opposed to starting with an arbitrary point in the funnel.

Go forth and optimize (for throughput)

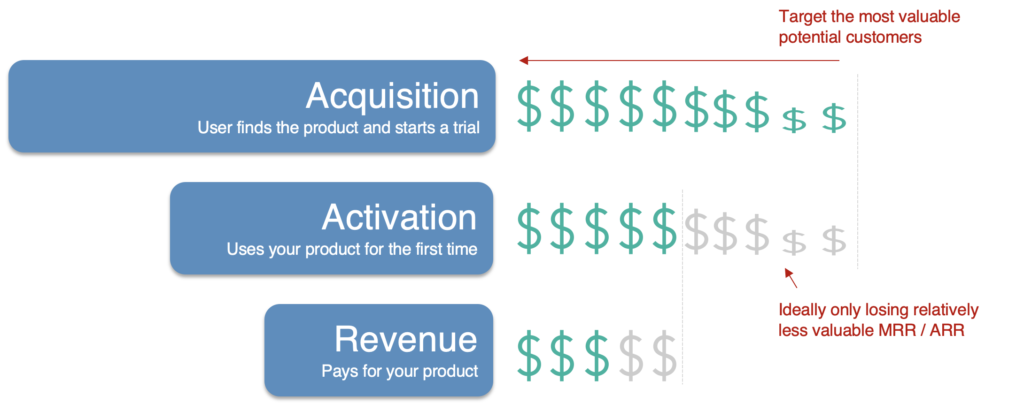

The principles described above apply regardless of whether you are focused on the number of customers or revenue metrics such as Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR) or Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR). Unlike the earlier example where all customers were equal, maximizing ARR requires that you target the customers who are the most valuable. Ideally, you will only lose the MRR or ARR that is relatively less valuable.

The bottom line: whether you’re focused on growing customers or revenue (or any other metric for that matter), you must not fall into the trap of optimizing random parts of the funnel without a strategy. Your goal is to maximize throughput of the funnel. And following the theory of constraints is one of the best ways to do it.